“You silly, silly creature! Get out of that oven immediately!” Impatiently I scolded Mr. Simms, our old tomcat, who always insisted on sleeping in the lukewarm oven.

“Someday that cat is going to be roasted alive,” I declared to Mama.

What nearly happened to our old tomcat nearly happened to my brother, Lou, and me. And we were supposed to have “more sense,” as Mama put it.

It happened one rainy morning. Hetty, my best friend, was sick in bed with measles, her house was quarantined, and I was forbidden to go near for at least three weeks.

I didn’t like rainy days, because there wasn’t anything interesting to do. I had two older sisters who helped Mama do the housework, so all that was left for me to do was tidy up my room and help with the dishes. That didn’t take long.

After a discouraging attempt to amuse myself by playing storekeeper with Lou, I gave up and sat dejectedly at a window watching the raindrops fall.

“Are you still moping about the rainy weather, Bonnie?” Mama asked as she came into the room. “Well, the rain’s letting up, and I need bread and cookies from the bakery. Here’s the list and the money. Take Lou with you, and don’t forget your umbrellas.”

Lou and I were delighted. It was always fascinating to go to the bakery and watch the giant mixers turning mounds of fresh, sweet-smelling dough, and see Mr. Hudson, the baker, in his white apron and cap, cutting, molding, and patting big lumps of dough into the shiny bread pans.

But our greatest excitement came when the bread was done and the baker opened the giant ovens. With the use of long-handled paddles he would take out the golden loaves that crackled with warmth. The delicious smells always made my stomach hunger for a thick slice right there and then.

In no time at all Lou and I arrived at the bakery shop. We walked in and set down our umbrellas to drip. But the shop was deserted! Then I remembered it was the noon hour.

“Aren’t we bright?” I said. “What will we do now? Mr. Hudson’s probably having dinner in his house next door.”

“Let’s look around,” Lou said. “We can go see the cool oven while we wait for the baker to return.”

“What’s a cool oven?” I asked.

“The baker has three ovens,” Lou explained. “Two are for baking bread and cookies. The other one’s fancier. It has a tile floor, and it’s used for baking soda crackers. Mr. Hudson doesn’t use it very often, only when he gets a special order. That’s why it’s called a cool oven. It’s shut off from the furnaces below by big sheet-iron dampers.”

I didn’t understand everything he said, but I was curious.

Mama’s kind friends said that I was a very observant child. But Mama flatly declared that I was much too curious for my own good, and that someday, unless I used good sense, I would find myself in great difficulty. “Curiosity killed the cat,” she would say.

Without thinking, I raised the latch of the heavy iron door and peered into the cool oven. “Why, it’s just like a cave, isn’t it, Lou?”

“Let’s crawl in and pretend we’re pirates or hibernating bears,” suggested Lou.

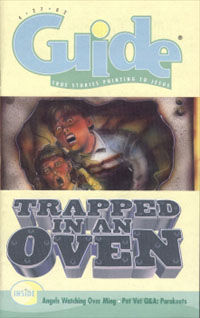

“That’s a good idea!” I clumsily climbed after him into the gloomy interior of the cool oven. We sat in silence for a few minutes. Then suddenly the iron door closed behind us with a resounding clang. Only a sliver of light shone inside, between the door and the doorjamb.

“Oh, Lou!” I cried. “We’re locked in! We’ll suffocate! We’ll die!”

“No, we won’t,” he said. “All we have to do is shout. The baker will let us out.”

Lou yelled and yelled for Mr. Hudson. He kicked the oven door, but to no avail. The baker had started the other two ovens, and the noise of the machinery drowned out our frantic cries.

Unless we were rescued soon, the air in our cave was bound to become stale. Already our throats felt dry and hoarse from yelling. And because of his height, Lou was forced to stay in a half-bent position that strained his back. Again and again we shouted and pounded on the oven door, but no one came to let us out.

I began to sob, and Lou put his arm around me. “Don’t cry, Bonnie. Perhaps the baker will hear me this time.”

Lou yelled and kicked all over again. But no one answered.

Suddenly we were startled by a scraping noise, as though a damper was being opened beneath us. A breath of hot air fanned our cheeks. If I had been afraid of suffocating, I was now doubly afraid–of being roasted alive!

“Oh, no!” I cried. “Mr. Hudson is heating the oven! We’re really going to die now!” I was terrified. “Now we’re worse off than our old tomcat ever was!” The grim joke helped make us feel a bit better.

“Don’t give up hope yet,” Lou said. “We’ve been in here only a few minutes. Perhaps heating the cool oven was a mistake, and the baker will close the dampers.”

But the tile floor of the oven was getting hot to the touch. Fortunately Mama had made us wear our heavy shoes that rainy day. We crouched on our heels or stood up as best we could, not daring to touch the walls or the roof with our hands and heads.

The air was getting quite stifling now, and my hair became damp and clung to my sweating cheeks. Poor dear Mama. We’ll never see her again, I thought.

“Oh, Lou,” I said out loud, “let’s pray for help! God always hears the prayers of children. Mama said so.”

While we said a short frantic prayer, I dug both fists into my apron pockets. My right hand touched Mama’s bakery list, and right then I thought of an idea.

“Lou, do you still have the pencil and string that you used when we were playing storekeeper this morning?”

“Yes,” he said. He fished them out of his pocket. “But what are you going–”

“Quick, then,” I said. “Punch a hole in this paper with the pencil, and tie the string through. Do you have a match?”

Just how he happened to have one, I don’t know, because we were never allowed to play with matches. But he had one.

“Give it to me,” I said. “When I strike it, write HELP on the back of this shopping list.” I struck the match and in the flickering light Lou wrote.

The match went out, and we were in darkness again.

Lou asked, “What are you going to do with all this?”

“The door,” I answered faintly. “Dangle the piece of paper up and down in the crack between the door and the doorjamb.”

Painfully Lou knelt at the oven door and slid the paper through the crack. Holding the string, he pulled the paper up and down to attract the attention of the baker or other occupants. But nothing happened.

Lou kept jerking the paper up and down, up and down. Once I heard him suck in his breath, and I knew it was because of the searing pain in his knees. After what seemed ages to us, but was really only a few seconds, we heard a muffled yell.

The latch lifted, the door flew open, and we fell into the arms of the terrified old baker. A window must have been open, for I felt my lungs slowly filling with pure fresh air. Dr. Harrison was called, and in a few minutes he was applying mentholated bandages to our burned hands and knees.

“I received an order for soda crackers. That’s why I heated the cool oven,” the baker explained to Dr. Harrison. “How was I to know that these children were hiding inside my oven?” The poor man! He was really very patient with us, considering how silly we had been.

The doctor took us home, and Mama nearly fainted at the sight of our bandaged hands and knees.

“Your children are fine,” the doctor explained, “just fine, except they won’t be playing ball for a while.” He handed her two loaves of bread and a dozen sugar cookies. “These are a gift from the baker.”

Our painful burns were punishment enough and a lesson that we would not soon forget. Indeed, we recalled the lesson painfully every time we went to the bakery!

It was weeks before I was able to see my best friend, Hetty. Dr. Harrison had told her all about what had happened. When finally we did get to see each other she scolded me soundly.

“What made you do such a silly thing?” she said. “Oh, I know. It was your curiosity.

I do suspect that you’ve no more sense, after all, than Mr. Simms, your tomcat. But I’m glad you didn’t turn into a burnt soda cracker!”

“And I’m glad you’re over the measles at last,” I said. The danger was passed. We both laughed.

But I have often wondered since I have grown older what would have happened if I

hadn’t thought about using the shopping list and Lou’s string. And I have never forgotten that the idea came to me while Lou and I were praying.

Reprinted from the July 31, 1968, issue of Guide.

Illustrated by Joe Van Severen