If you missed any of this continued story in Guide, here’s where you can catch up.

Chapter 1

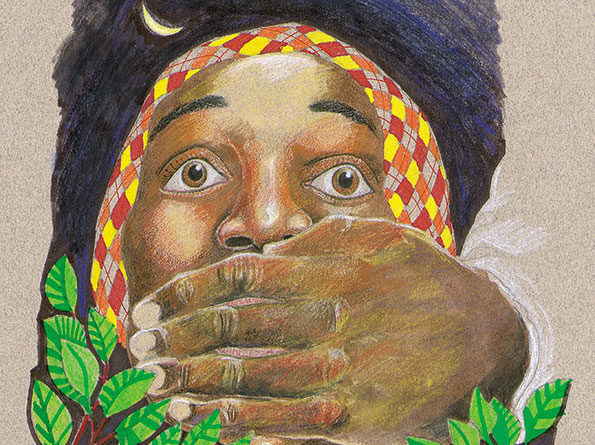

They were almost there that night when Caesar suddenly grabbed Harriet and pulled her into the bushes. His large left hand cupped her mouth and chin, but her eyes, large with shock, looked questioningly at the burly coach driver.

Peering anxiously down the dirt road, Caesar raised his right hand, beckoning Harriet to get down. Then he lowered his other hand from her face.

Harriet froze, trying to make out the danger that her traveling companion saw in the Maryland countryside. Then she heard it. The drumming of horses’ hooves rapidly approaching them. Patrol riders!

Harriet caught her breath. She didn’t want them to see her and Caesar. If they did, they would demand the pass allowing them to be out from their master’s plantation this late. They had no pass.

Harriet was sneaking off to see her 1-year-old son, who lived on another plantation from the one on which she worked as a field hand. Caesar was one of the male slaves who accompanied her from time to time for protection.

If the patrol riders discovered their mission, they would cart the pair off to their master. They would be in big trouble and would get a whipping—or worse.

The patrol riders brought their horses to a halt near the slaves’ hiding place.

“Thought sure I saw something moving near the road and then dart into the bushes,” one of them drawled, less than 15 feet away from the trembling Harriet.

“Probably just your imagination, Bill,” his partner responded, glancing about and seeing nothing. “Or it could have been a deer. In the dark their antlers sometimes make them look human, especially when they’re moving fast.”

“But it looked like two persons.”

“Well, it could’ve been a doe and a buck. They often travel together.”

Not quite satisfied, the other man drew his pistol and advanced toward the bush in which Caesar and Harriet were hiding. She felt Caesar tensing, readying himself to charge the man if they were discovered. Sweat beaded on Harriet’s forehead. She couldn’t be caught.

Dear God, she implored, please blind him to us. Fred needs me so!

The slave catcher stopped six feet short of the pair, but after a moment skirted around them. Finally he retreated toward his waiting partner.

“Guess you’re right, John,” he sighed. “Been so long since I’ve caught a slave that I’m mistaking animals for them.” He chuckled, bending forward and patting his horse’s neck.

“Gets that way sometimes,” the other man consoled. “Don’t worry, though. God’ll help us break this dry spell. He knows we sure need the money we get from catchin’ slaves.”

With that, the men turned their horses away from the clump of bushes, vanishing in the direction from which they had come.

Chapter 2

After the hoofbeats died away, Caesar motioned for Harriet to get up.

“Sorry about covering your mouth. Hope I didn’t hurt you none.”

“No need to apologize. I’m just fine. Just happy you heard them.” Harriet smiled as they again entered the roadway. “If it hadn’t been for you—” She trembled at the thought of being deprived of seeing her little Frederick.

During the rest of their secret journey the two slaves uttered not a word, so ill at ease were they by their narrow escape. Forever glancing far down the road and at some distant spot ahead, they seemed not to hear the rising chorus of insects, accompanied now and then by the soft cries of owls starting their nighttime hunt.

Even the striking beauty of sky and woods bathed in moonlight could not induce them to drop their wariness. They were ready at a moment’s notice to hide away in the bushes and emerge only when absolutely sure there was no danger.

Minutes of tension melted into relief when a tired Harriet saw the outline of her mother’s cottage. A rush of energy swept over her as she thought of her son.

Fred will be fast asleep, she thought. He won’t even remember that I’ve been to see him when he awakens in the morning. But that’s all right.

Every chance she had gotten over the past few months Harriet had walked the miles between the two plantations. She could do it forever, she told herself, just to see her growing son. To hear his voice, though muffled by drowsiness, as he murmured “Mama” and smiled up at her before drifting back to sleep. To know that he was all right, instead of relying on messages her mother sent from the Tuckahoe plantation.

If only there were some way Fred and I could be together again! she yearned.

“Well, praise God, we’re here,” Caesar sighed as they stood before the doorway of the shabby cottage.

“That we are,” Harriet responded, flashing a quick smile. “I couldn’t have made it without you. Fred and I are powerfully grateful to you for sticking by me tonight.”

“Oh, it’s nothing,” he said, almost sheepishly. “You’ve done me many a favor. I’ll never forget the times you got Hepsibah to sneak food out of the big house to me when I was hungry.” Harriet beamed at the memory of the huge man wolfing down the leftovers that she sometimes carried to his hut.

“Just enjoy your time with Fred and Miss Betsy. Tell her howdy for me. I’m going up the quarters a piece to visit some of my folk. I’ll be back directly.” With that, Caesar turned and walked toward a series of cabins some distance away.

Harriet watched him for a moment. Then she lightly rapped out a coded signal on the door. Her smiling mother whisked her into the one-room cabin.

Inside, she quickly spotted Fred huddled among several other children asleep on the earthen floor. Stepping carefully over the pile of legs and arms, she gathered her son in her arms.

Her mother motioned her to a vacant corner, where she could sit undisturbed. Harriet had just an hour with her son before Caesar’s own coded knock would signal her away.

Between kisses she stroked the child’s face and rocked him. In the light from the pine knotholes in the walls, she marveled at how much like her mother Fred looked. Peace filled her. Nothing seemed able to disturb it. Then she shuddered as she thought of the distance between her and Fred and the patrol riders watching the woods.

That’s no way to think, she scolded herself. God is still on the throne. He’ll make a way for us.

With that thought cheering her, she hugged Fred closer and smiled. The present was enough. God would take care of their future.

Chapter 3

Six-year-old Frederick stooped over six figures he had made from the Tuckahoe, Maryland,* mud. The four shorter ones represented him and his three siblings. Instead of the long shirts slave children usually wore, he and Perry had on shirts and pants, while Sarah and Eliza wore pretty dresses.

“We’re going to the North,” he said quietly to his creation, smoothing the mud forming Sarah and Eliza. “We’ll never be old master’s slaves there!”

The taller shapes represented the children’s mother and Grandma Betsy. They not only wore dresses like White women, but also sported shoes. According to Fred, they were all going to Annapolis, Maryland, and from there the family would board a big boat for New York.

Fred rose and stood back a little, examining the figures. Something seemed wrong with his little creation. He puzzled a bit and then suddenly saw what was wrong. He had made a mother, children, and even a grandmother. But someone was missing. There was no father. Why?

“Jemima and some of the other children tease me,” he said aloud. “They say I don’t have a papa. But that’s not true.”

One night, just before he drifted off to sleep, he had asked Grandma Betsy about it. She had turned her face away for so long that he feared that she would say that he did not have a father after all.

“You’ve got a father just like everyone else,” she had finally assured him. “God gives every child a mama and a papa.”

“But where’s my papa?” he persisted.

“Well, he’s around somewhere,” she said carefully, letting out a sigh. “But because he hasn’t been the kind of father he should be, God has decided to be a ‘double’ father to you.”

“How do you know that?” Fred had asked, his eyes wide with wonder.

She turned her face toward him. “Well, He told me so in the Book Peter reads to me when he gets the chance.”

“Will God tell me the same thing?”

Grandma Betsy smiled down at him. “He sure will when you get old enough to read what He says in His Book.” She patted Fred’s cheek, telling him to go to sleep.

A warm feeling had spread all over him then, for he felt special. He had God for a double father.

Later when some of the children pointed out how pale his skin was, Fred started wondering about his father again. Some of the grown-ups, he told Grandma Betsy, whispered that his father was a White man. Was it true?

“Yes, it’s true,” Grandma Betsy answered, “but I don’t know which White man.” And then she said something very much like what she had told him earlier.

“He’s not been the father that he should be. But God has said that He’ll be a father to the fatherless.” She had paused from her task of putting flat cakes into a stone oven to look squarely at him. “So that means He’ll take care of you all through your life.”

She reached for her apron to wipe the circles of sweat dotting her forehead. “And don’t you forget,” she continued between wipes, “that as long as I draw breath, I’ll be here to help you and love you.”

Fred looked up at her smiling face, confident that she would always be there for him.

*Tuckahoe was not a town, but an area in Talbot County, Maryland, that lies west of the Tuckahoe River.

Chapter 4

Another time Fred had run into the hut crying as if his heart would break. He hid himself in the folds of his grandmother’s long, billowing dress.

“What’s the matter, Fred?”

He drew his face away, attempting to speak, but his jaws trembled, and only gasps sounded. Grandma Betsy took him by the hand and walked over to a large rocking chair. She sat down and placed him on her lap. As she silently rocked, she hugged with one hand and patted his back with another. Soon the boy felt free enough from whatever was bothering him to speak.

“Is it true that my mother is a bad slave and was sold down the river?”

“Wherever did you get that idea?” Grandma Betsy cried in alarm.

“From Joseph. He said that’s why I’ve never seen her.”

“Fred,” she began, “don’t listen to a word the children say about your mother.” The rocking increased in speed, the old chair seeming to creak in agreement. “She is not a bad slave. She hasn’t been sold down the river. She’s on another farm several miles away.”

“Then why doesn’t she come to see me?”

Grandma Betsy halted, a faraway look clouding her eyes. “She would if she could, but it’s not that easy. The master on her farm won’t allow her to.” The chair creaked loudly.

“But you told me that she used to sneak off to see me when I was younger.”

“Yes, but it was easier then. Now she can’t. But as soon as she gets a chance, she’ll come.”

“Really?”

“Yes, you’ll see . . . you’ll see.”

With these memories coursing through his mind, Fred squatted beside the six mud figures. He would make a seventh one, he decided. This one would be larger than even Mama and Grandma Betsy. He would be powerful. But He wouldn’t give anybody whippings. He’d always have a smile on his face, just like Grandma Betsy. And He’d play with him and his brothers and sisters. This seventh figure would represent God. He would be the One to get them to the North and away from slavery.

“Fred,” a voice called out, interrupting his creation of the last mud figure. The boy hurried to finish it before answering.

“Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey,* where are you?” the voice called again. It was Grandma Betsy. Since she was using his full name, it must be something mighty important.

“Coming, Grandma,” he yelled, leaving the gigantic figure armless.

Fred ran toward the house, avoiding the puddles that had formed on the path from last night’s rain. He made a mental note to splash in them after hearing what Grandma Betsy had to say.

“Yes, Grandma Betsy?”

“We’re going somewhere special today.”

“Where?” he asked excitedly. He hoped that she would say the North, and that his mother and siblings were coming too.

“Today we’re going to the big plantation at Wye River.”

The big plantation at Wye River? That was almost as great as going to the North! He would get to see his brother and sisters. He would also see the great fields of vegetables that Grandma talked about. Plus the wagons and new faces and big buildings. Best of all he’d get to play at the windmill with his siblings and other children who had once lived near Grandma Betsy. He couldn’t wait to go.

Strangely, Grandma Betsy didn’t share his excitement.

“Don’t you want to go, Grandma Betsy?” he asked, noting the sad, faraway look in her eyes.

“Well, Fred, it’s something that has to be done. And the sooner we get it over with, the better . . . for us all.”

The sooner we get it over with, the better? What did she mean? Strange words to say just before going to see his brother and sisters. However, Fred’s excitement about visiting the big plantation didn’t allow these perplexing thoughts to lodge in his mind. They were soon replaced with visions of food, fun, and friendly children his own age.

He looked in the direction of the faraway plantation and wished he were there already.

*Frederick later changed his last name to Douglass to help avoid being caught.

Chapter 5

Along the way to Wye Plantation Fred noticed that Grandma Betsy seemed preoccupied, but it didn’t really bother him. He figured her mind was on a grown-up subject, such as work or getting the food that she always seemed to come by.

The day wore on, the sun became hotter, and the distance they traveled stretched into mile after mile. The boy’s spirits began to droop.

“Grandma, I’m afraid,” he announced as they entered a forest they had to pass through before reaching their destination. It seemed to him that hidden behind every tree were animals ready to pounce on them or patrol riders itching to sell them downriver.

“I’m right here, Fred. Take my hand.”

He squeezed it tightly and was instantly reassured. But his legs seemed more tired than they had ever been before. He wished that they had never started out for Wye. If he had stayed, he would have finished making the arms for his seventh mud figure. By now he would have been playing with his friends or resting in the shade of a big tree.

“Grandma Betsy, I’m tired,” he appealed. “I can’t go another step.”

“Old Master wants me to be at the big house soon,” she explained. “We can’t stop to rest now.”

Fred’s face, steamy with sweat, sagged disappointedly.

Grandma Betsy smiled down at him. “I’ve got a grand idea. Why don’t you hop on my shoulder?” she suggested, bending low.

A horsey ride! Fred scampered up, all smiles. “Thanks, Grandma,” he said, feeling instant relief, as well as love. Perched on her shoulder, he felt far away from his earlier fears.

As they neared the plantation, pride forced him down from his comfortable position. He didn’t want the children of Wye Plantation to say he was a big baby. He had enough teasing from the children of Tuckahoe Plantation.

When they arrived at Wye Plantation, they were surrounded by children, all seeming to speak at once. Never had Fred seen so many children in one place! They were of all ages. Girls and boys. Short and tall. Slim and chubby. Pushing, pulling, and clamoring for attention. With features from ebony to brown to almost white. Fred noticed they called his grandmother Grandma Betsy, just as he did.

Disentangling herself from the embrace of two girls and a boy, Grandma Betsy explained to him, “These are your sisters, Sarah

and Eliza, and the boy here is

your brother, Perry.”

Grandma Betsy scanned the forest of faces smiling up at her. “Most of the children are kin to you.” She patted the heads of several boys and girls, relaying their names to Fred.

He gave each of them a shy smile. They giggled in response and jabbed each other in the ribs or pointed at the little newcomer with great pleasure.

“Fred,” Grandma Betsy said wearily, sadness stealing into

her voice, “go and play with

them. I’m going to see some

folks.”

The 6-year-old suddenly felt vulnerable and clutched her skirt.

“It’s all right, Fred. Remember that most of them are your kinfolk. I’ll be back after a while.”

Sarah and Eliza stepped forward, taking hold of his hands and promising that they would teach him some new games nearby.

“Yes,” piped up Perry, “and

then we’ll climb trees for pears and peaches!”

Fred relaxed and followed his sisters and Perry into the group of laughing children. Soon he felt as if he had known them all his life.

But all was not as it seemed.

Chapter 6

Fred was having so much fun playing with children in his own age group! The little children at Tuckahoe are never as much fun as this, he thought as he ran to tag a whirling girl trying to elude him. Best of all, none of his new friends teased him about his color or his parents.

All too soon the games ended, with Perry’s voice drifting over to the contented boy. “Fred, Grandmammy’s gone.”

“Gone? Gone where?”

“To Tuckahoe.”

Fred shook his head in disbelief. Grandma would do no such thing! She had promised that as long as she had breath, she would be there to help him and to love him! Shrugging off Perry’s comment, Fred attempted to resume his play. But he felt Perry’s hand on his shoulder, turning him around.

“It’s true, Fred. Grandma has gone back to Tuckahoe.”

“She can’t go,” Fred countered. “I’m still here. Plus she said she’d be back after a while.”

Sarah stepped forward. “No, Fred. She had to go back without you. She only came today because Old Master told her to bring you to Wye.”

“Whenever you’ve seen six or seven summers, he sends to get you from Grandma Betsy,” Eliza explained. “The old folks say it means you’re old enough to start being a slave.”

“But I won’t let her go without me! I won’t, I won’t, I won’t!”

The now-distressed boy tried to penetrate the wall of children gathering around him.

“I’ve got to get back! She needs me to run errands. No one will be there to thread her needle for her. Who will help her weed her garden? Plus, I haven’t finished making the arms for God!” His mind raced back to the mud figures he’d left behind at Tuckahoe.

The older children exchanged confused glances, but Sarah hugged Fred, whispering, “It’s all right, it’s all right. It’s not so bad here once you get used to it.”

“And I’ll be right here to help take care of you,” assured Perry, sealing his promise with a few peaches that he offered his younger brother.

Looking angrily at them, Fred drew back an arm and with a powerful blow sent the gift flying.

“I don’t want your fruit!” he shouted. “I want Grandma!”

Again Sarah hugged him, this time joined by Eliza and Perry.

“I know, Fred,” she sympathized. “I felt the same way when Old Master sent for me.”

“Me, too,” chorused Perry and Eliza.

The admission, instead of comforting Fred, made him feel trapped. In a new round of tears he buried his face in Sarah’s shoulder.

“It’ll get better, Fred,” she murmured. “It’ll get better.”

“You’ll see,” agreed Eliza and Perry weakly.

The other children slowly scattered toward their cabins. Through his tears Fred wondered whether he could trust anyone again.

Chapter 7

It’s almost time, nine-year-old Fred thought, tracing a twig in the riverbank’s soft soil. Surely the stomach pains and lightness in his head would ease a bit then.

He looked over at the other children. A few girls were playing clapping games and dodgers by the windmill. Four or five boys were skimming stones on the river’s surface, then gathering more to see who could throw them to the opposite bank.

Fred wanted to join the boys, but he knew he would be no match for them. Unlike them, he had eaten neither breakfast nor lunch because he was being punished again by Aunt Katy, the plantation cook, for something she claimed he had done.

Fred remembered how his mother had confronted her about depriving him of food. He had been huddled near the open fire, about to eat a few corn kernels he had just finished roasting. He must have looked dejected because his mother asked him what was wrong.

Fred glanced in Aunt Katy’s direction but remained silent.

Fred’s mother gathered him in her arms and whispered, “Don’t worry, Fred. If someone’s making you sad, tell me. I promise I won’t let them hurt you.” She patted his back so lovingly that he believed her.

“It’s Aunt Katy,” he whispered. “She hates me. Sometimes she says that I did things that I didn’t do. And when I tell her that I didn’t do them, she gets angry and doesn’t give me food when she feeds the other children.”

“What!” his mother responded, her voice rising.

“She says that she is going to starve the life out of me.”

Enraged, his mother marched up to Aunt Katy, who was no longer the domineering tyrant that she had been to Fred. The cook took a step back from the advancing mother.

“Katy,” Fred’s mother began, “how dare you starve a growing child! How do you expect him to grow into one of Old Master’s field hands? If he gets wind that you’re starving one of the children, you know what he’ll do to you. In fact, I have a good mind to tell him about it right now!”

Aunt Katy’s facial expression changed from one of fear to that of absolute terror, especially at the mention of what Captain Aaron Anthony would do to her.

At the sight of the cringing woman before her, Fred’s mother relented. She took a deep breath and stepped back herself.

“I know Fred’s not perfect. And he’s inclined to disobey and be mischievous, just like any other child. But Katy, no child deserves to be starved for that kind of behavior!” She shook her head from side to side. “A spanking now and again, but surely not starving!”

Satisfied that her threat would change Katy’s behavior, she rejoined Fred. He quickly climbed into her lap after she had sat down. She took away his little store of kernels and reached into the folds of her dress. She took out a package and opened it slowly, looking mischievously from him to it all the while.

“A ginger cake!” he chirped as the last layer of paper was unwrapped. He hugged her and at once started eating the large treat.

As the last mouthful disappeared, along with his hunger, he felt special. No, he was not a little devil, as Aunt Katy claimed he was. He was just like any little boy. Most of all, he was somebody’s child, and he would never forget it.

Chapter 8

As time passed, hunger pangs once again engulfed Fred. Oh, how he wished that his mother were around. But Mama’s dead now, he reflected.

Fred switched his attention to the sun moving along in its downward descent to the west. I’d better get going. It’s about time.

A shortcut through a field soon saw him near his destination: Old Master’s house. He hid behind a shed, waiting for a slave girl to come from the kitchen.

Just when he thought he had missed her and was about to leave empty-handed, he saw the portly 10- or 11-year-old emerge with a bowl of dinner scraps. She walked about ten yards, then emptied the leftovers onto the ground. She then turned and hurried back to the kitchen.

When he was sure the girl would not return, Fred slunk toward the pile of bones, pieces of chicken, half-eaten cornbread, and collard greens. He ate furiously, looking right and left, as though expecting someone to drive him away.

His fears were realized when a bundle of brown hurled itself toward him, grabbing at the bone in his hand. It was Old Nep, the Anthonys’ family pet! The dog growled threateningly. Its curled lips revealed sharp incisors, and the hair on its back rose. Looking fearfully at the angry dog, Fred retreated to safety.

As Fred watched the dog devour the scraps and then scamper away, he lowered his head and cried. Not silently but noisily. So noisily that Lucretia Auld, Old Master’s daughter, came out to investigate. The young woman’s heart crumbled at the sight of the weeping child.

“Come here, boy,” she said gently. She stretched a hand to him and smiled. Encouraged, he came forward.

“What’s the matter?” she asked. She got no response, but signs of the evening’s dinner on the slave boy’s face and the memory of a growling dog answered her question.

“Stay here a minute,” she said. “I’ll be right back.”

Before Fred could gather his wits and escape to the slave quarters, Lucretia returned. Balancing a plate with two thick slices of cornbread, she sat down on a step and motioned for Fred to join her.

“I didn’t get enough to eat at dinner, so I’m having a bit more. Want to join me?” She extended a hunk of cornbread.

Wordlessly, but with a grateful look at her, Fred took it in both hands and gobbled it.

“That was quick!” said Lucretia with a smile. She tousled Fred’s hair, and he smiled back.

“Why not have some more?” she offered.

He didn’t want to eat her share, too, but he was so hungry! And she was nice—nice in a way that reminded him of his mother.

“I can always get more inside,” Lucretia prompted.

Fred accepted the last slice, finishing it almost as quickly as the first.

Lucretia’s generosity and acceptance so warmed his heart that Fred now answered her questions readily. No, he did not have a father that he knew about—only God. His mother was dead. He had two sisters and a brother, but they were now old enough to work in the fields from sunup to sunset, so they did not see much of each other. He did have a grandmother, but he hadn’t seen her since she had brought him to Wye Plantation a long time ago.

What did he want most of all? To have his mother back! Next he wanted Grandma Betsy, Sarah, Eliza, and Peter to be with him always. And maybe his father—but he had never seen him.

The boy prattled on and on, as if telling the young woman everything that he wished he could tell his mother. He told Lucretia about school. Uncle Isaac Cooper taught him and the other slaves. He taught them the Lord’s Prayer and told them to obey their master, Captain Aaron Anthony. Their Master in heaven wanted them to do so, he explained.

No, Fred didn’t work in the fields. He was still too little to do so, although sometimes he carried water to the field hands. But what he loved most was playing with his friends near the slave quarters or by the riverbank and the windmill.

Lucretia looked with amazement at the intelligent and suddenly talkative youngster! How transformed he was from the waif of an hour ago. He seemed too bright to be a slave! All it took, she thought, was a little love and food.

When Fred finally finished telling her all about himself, he stood up. “Thanks,” he said, giving her a winning smile.

“You’re welcome, Fred.” She drew him to her side, hugging him briefly and telling him to come back and see her again.

Still smiling, he turned and walked homeward. Just before he was out of the yard, he looked back and waved with a flourish.

Lucretia laughed and waved back. As she watched him retreat out of sight, she repeated aloud, “All it took was a little love and a bit of food.” With the slave boy heavy on her mind, she mounted the steps and went inside.

Chapter 9

There it is again! Lucretia sat still in her bed, straining to make out the sounds. Music! But not from the family piano. It was mournful yet thrilling. Like the songs she heard the field hands sing when they came in from work. Hurriedly she put on a housecoat and poked her head outside the window.

It was Fred with an impish grin on his face, moaning and singing like Uncle Jeems, the plantation fiddler!

“Fred, what are you doing up so early?” she asked with a yawn.

“I just wanted you to hear how well I sing,” he said sheepishly.

She noticed that he looked toward the kitchen as much as he did at her. The child’s hungry, she thought. Aunt Katy must be holding back food again.

“I’ll be down directly to hear some more of your singing,” Lucretia said, smiling down at Fred.

Ten minutes and two quickly eaten hunks of corn bread later, Lucretia sat on the porch with her early-morning visitor. Fred was brushing pieces of corn bread from his lips.

“Fred, how would you like to go to Baltimore?”

“I sure would!” Fred replied, his eyes sparkling at the thought of the big city. His cousin Tom had visited Baltimore. Ever since then nothing at Wye Plantation could compare to it in Tom’s young eyes.

In Baltimore there were steamboats. Its ships could swallow Captain Auld’s sloop, the Sally Lloyd, four times! He had even seen firecrackers, soldiers, and stores with tons of great things in them. As Fred listened to Tom describe Baltimore, he longed to go there too. He was sure that in this magical city he would find happiness.

Looking up at Miss Lucretia, Fred asked, “Are you going to Baltimore?”

“No, but you are.”

“Really? How come?”

“Well, my sister-in-law, Mrs. Hugh Auld, lives there. She and her husband need a bright, hard-working

boy to help take care of their little son, Tommy.” She paused a moment, gravely looking down at the wide-eyed Fred. “Are you that boy?”

“Sure am!” the almost 10-year-old youngster immediately replied.

Lucretia smiled at his enthusiasm. “I know you are. But you need to know that the folks in Baltimore are very clean. They’ll laugh at you if you aren’t clean too.”

Fred’s grin disappeared. He looked at the plantation scurf covering his arms and legs and hung his head.

“You’ll have to go to the river and get rid of the dead skin on your feet and knees, too,” Lucretia continued. “If you do, I’ll give you a pair of trousers to wear to Baltimore.”

Trousers! Fred’s grin reappeared as he raised his head. He fingered the long shirt that was his only article of clothing. He would bathe in the river a thousand times to discard it for his very own trousers!

Three days later Fred boarded the boat for Baltimore and took a last look toward Wye Plantation. It was there that he had been separated from his grandmother and had witnessed brutal slave beatings. Memories of constant hunger, Aunt Katy’s meanness, and his mother’s death all flashed before him.

I’ll not miss it, he told himself. Only Miss Lucretia. He sighed as he remembered her giving him hunks of corn bread and bandaging his head after a fight with another slave boy. With that he turned his back and looked toward Baltimore.

At the big city Fred could not believe his good fortune. Mrs. Sophia Auld seemed to be his mother, grandmother, and Miss Lucretia all rolled into one! She treated him as a normal child and not a slave. In fact, she acted as if she had two sons: her natural child, Tommy, and her newfound son, “Feddy.” When putting Tommy to sleep on her lap, she was sure to have Fred close by her side, listening eagerly as she retold Bible stories.

Mrs. Auld trusted him unquestionably with Tommy. “Feddy is here to take care of you,” she reminded Tommy from time to time. “He won’t let anything hurt you, and he’ll always play with you.”

In this healthy atmosphere Fred blossomed into a happy, carefree lad. Sometimes, when he thought of his days at Wye Plantation, they seemed like a nightmare from which he was awakening at last.

But trouble lay on the horizon.

Chapter 10

Things were going well with the Aulds. But that all changed one afternoon when Mrs. Auld, with a smiling Fred at her side, proudly told her husband how she had taught him the alphabet.

“Sophia, what have you done?” he stormed in disbelief.

“Why, Hugh, I’m only teaching the child how to read.”

Her husband rolled his eyes.

“Feddy has a good mind, dear,” she explained. “He already knows how to read simple words.” Hugh Auld caught his breath at this revelation, but she continued, “Pretty soon he’ll know enough words to read the Bible. Won’t that be a comfort?”

Mr. Auld at last found his voice and broke into a tirade.

“No, it won’t! It’ll be a curse! If God had wanted slaves to read, He wouldn’t have made them slaves. Plus, your little experiment is against the law. You—we—could all be in trouble for this. If Fred learns any more, he’ll be spoiled for life.”

He stopped to put his hand on his wife’s shoulder. Then he spoke slowly to emphasize his next words. “If you give a slave an inch, he’ll take a mile!”

The man moved away to stand before the frightened child. “Reading will make Fred discontented and unmanageable. Pretty soon he’ll be writing passes to escape to the North.” He paused, moving back to his wife. “And Tommy? Why, he’ll be without a caretaker!”

The wince in his wife’s eyes showed that his words, particularly the last ones, had achieved the desired effect. Just to be sure, he concluded, “All that boy needs to know is how to obey his master—and how to work! Nothing less, nothing more.”

From that day Mrs. Auld ceased her experiment with Fred. In time she became extremely opposed to his education. If she saw the boy with a book or newspaper in his hands, she would furiously snatch it from him. “That’s not for you!” she would storm, tearing the newspaper into shreds.

If he was in a room by himself for a length of time, he was sure to hear, “Fred, Fred, come here!” He would immediately go to her to see what she wanted. More often than not, it would be about some trifle. Or she would create work for him when clearly there was no need for it.

She thinks I’m trying to read, he realized after it happened a few times. She wants to keep me from it.

In fact, Mrs. Auld was as determined to uproot her former pupil’s ability to read as she once had been to plant it.

Chapter 11

Fred tossed on his bed, trying to fall asleep. But Hugh Auld’s prohibiting Miss Sophie’s tutoring sessions troubled him: “If God wanted slaves to read, He wouldn’t have made them slaves. . . . If you give a slave an inch, he’ll take a mile. . . . Pretty soon he’ll be writing passes to escape north. . . .”

What did these words mean? Why was Master Hugh so angry about something that made him so happy—something Master Hugh and Miss Sophie wanted Tommy to learn? Why did Miss Sophie turn into his tormentor the instant that books were anywhere near him?

After several more minutes of tossing and turning, Fred finally came up with an answer: They’re trying to keep something important from me.

During the seven years that he lived with the Aulds, Fred secretly tried to find out what it was. He stuffed his pockets with biscuits whenever he went out to play with White neighborhood boys. He would give them a biscuit or two in exchange for a lesson in reading and writing. By the time he was 13, he could read remarkably well.

Not only that, Fred also had secret access to Tommy’s schoolbooks. He practiced writing the lessons that the boy learned daily in school, until his handwriting was very much like Tommy’s.

To his surprise, his advancement in learning brought him something else. It awakened him to his condition as a slave, especially as he read The Columbian Orator, a book he had secretly saved his pennies to buy. He learned that God had created him with just as much a right to be free as his White friends. He was entitled to all the privileges that they enjoyed but that society withheld from him.

But while Fred’s newfound education taught him all of this, it did not show him how to get these rights for himself. It was like placing a starving boy before a banquet table, then refusing him service because he did not have money to pay for the food.

As a result, Fred became very depressed. He wished he had never learned how to read. Sometimes he wished he were dead.

During this time Fred started going to church. The preaching of Reverend Hanson, a White Methodist minister, awakened him to his condition as a sinner. Regarding his state as a slave, however, the boy did not clearly know what to do about it.

One evening after church Fred worked up the courage to speak to Charles Johnson, a kindly Black Christian who seemed to like children. A few older people had gathered around the man, and Fred feared that he would not get a chance to see him that evening. Sometimes the adults’ talk could turn into debates that lasted an hour or more.

Fred stood a few feet away

in the shadow of a church wall, trying to appear uninterested in the little group. Inwardly he prayed for their conversation to stop so that he could ask his questions and go home in time to prepare Tommy for bed. After what seemed like forever, he heard the adults take their

leave of each other.

Fred took a deep breath and hurriedly caught up with Charles Johnson. “Brother Johnson,” he began, “may I

ask you a question?”

“Of course, child.” He smiled and put his arm around the boy’s shoulders. “What’s the matter?”

“I am a sinner, and I want to be good. I want to love Jesus and to go to heaven, but I don’t know how! I’m scared that I’ll never know how!” The words poured from him in a torrent

of emotion.

“Fred,” the older man said softly, “you needn’t be afraid.”

The boy looked at him in surprise.

“What you’re feeling is the conviction of God’s Holy Ghost. God is trying to get your attention. He wants you to be dissatisfied with the way you are now and to come to Him for cleansing and conversion.”

“But how?”

“Just go to Jesus and ask Him. Tell Him that you’re a sinner and that you want Him to forgive your sins. Then ask Him to change you so that you love and serve Him. Tell Him that you also want to love and help others. He’ll hear your prayer.”

“Is that all? Don’t I have to do anything first?”

“No, child. Just have faith

in God. Do what I say and read the Bible. Believe it. God will do the rest. You’ll become a new person and have peace in

your heart.”

Fred followed the man’s advice. As a result, Fred became a Christian. The Aulds were quick to see the change in him. His depression vanished. His heart was filled with joy. He looked at things differently. His heart overflowed with love for everybody—even slaveholders.

But although he loved slaveholders, he still detested slavery. He fretted for a way to bring it to an end.

Chapter 12

It was at this time that Fred met Mr. Lawson, a Black Christian who was also a horse-and-carriage driver. Fred admired the elderly man’s habitual prayer life and respectfully called him Father Lawson. He often went to Lawson’s home.

Fred shared his education by reading the Bible for the almost-illiterate man. Lawson for his part imparted something of great value to the lad. He became the father that Fred had never known and watched over his Christian growth.

Despite Hugh Auld’s threat to whip him if he continued to visit the free Black man, the youth felt drawn to him. Throughout his life he would cherish Lawson’s example and high hopes for him.

“God has a great plan for your life,” Lawson told the boy one evening. “He made you to be a useful man. In fact, He has shown me that you’re to be a preacher of His gospel.”

“But I’m a slave!” Fred protested, squirming uneasily before the elderly man’s searching gaze.

“Don’t worry about that, son. If God wants you to do something, He’ll help you.”

Fred paused, considering the full meaning of Father Lawson’s words. “What I want more than anything in the world is to be free!”

Lawson smiled. “Well, it’s just as the verse that you read to me says: ‘Ask, and it shall be given you; seek, and ye shall find’ ” (Matthew 7:7, KJV).

“How do you know that?”

“I’ve lived many a year, and I’ve never seen God’s Word fail. Your freedom may not come today or tomorrow. But it will come. Just read your Bible, trust Him, and continue to grow in Him. When it’s time, He’ll show you how to get your freedom.”

He paused and looked at Fred without a trace of disbelief. “He’ll do it,” he emphasized, tapping his open left palm with his right index finger, “just as He did it for Moses and the children of Israel! Just get ready. Get all the learning you can. That way you’ll use your freedom well when it comes.”

Fred looked carefully at the old man, who was now smiling. Father Lawson had never lied to him before, not even about little things. He did not believe that he would do so now—especially about something so important.

Fred’s faith in Mr. Lawson proved to be well-placed. But just ahead, more challenging times awaited young Frederick Douglass.

Chapter 13

Suddenly everything changed for the worse. Old Master had died and not left a will behind. That meant Fred had to return to Wye Plantation from Baltimore to be valued with the rest of the deceased man’s property. Gone suddenly was the less taxing form of slavery that Fred had experienced in the city. Gone were his happy days with Mr. Lawson, the Aulds, and his young friends.

Afterward, it had to be decided whether he would fall to Lucretia Auld’s share of the inheritance or her brother Andrew’s. Fred prayed that he would fall to Lucretia, for young Andrew was fast becoming a drunkard. He also had a violent temper that he had no reluctance in expressing to the slaves. He stomped Fred’s brother mercilessly when Perry dallied instead of coming when Andrew called him. After the stomping left Perry writhing in pain, Andrew turned to Fred and said, “I’ll give you the same treatment if you ever get into my hands!”

Fred trembled upon hearing the threat. Should his lot fall to Andrew, not only would he never return to Baltimore, but he could also be beaten to death.

Providentially, Fred’s fears did not materialize. After a month at Wye, Lucretia assumed ownership over him. By this time she was the mother of a little girl herself and knew how badly her sister-in-law and little Tommy missed and needed Fred. The evaluation and division of her father’s property now over, she sent Fred to Baltimore again, with her husband’s agreement.

Now happiness and relief such as he had never before experienced in his life flooded Fred. Baltimore’s outline rose in the distance as the boat approached the harbor. Fred was beside himself with joy when familiar buildings came into view. How happy Mr. Lawson would be to have him back! He made a mental note to thank the elderly man for praying for him. His neighborhood friends, who were becoming more and more like brothers to him, would celebrate with him.

Fred grabbed his small bundle of clothes and jumped down from the boat as soon as it docked. Looking at a row of carriages for hire, he fingered the coins that Miss Lucretia had given him for carriage fare. No, he would not use them, he decided, shaking his head. Riding a horse and buggy through Baltimore’s busy roads would take longer to reach home than if he walked. Instead, the money could buy something for his little party. Walking swiftly, he headed for home, deeply breathing in the city’s salt-sprayed air and whistling a cheery plantation tune.

The Aulds were overjoyed to welcome him back. Tommy ran to embrace him. Mrs. Auld’s eyes shimmered with tears. And Mr. Auld furtively cleared his throat and looked away. Even though the Aulds had prevented Fred from learning to read, they still loved him. Fred prayed that he would never again be separated from them and his friends.

But a few years later 16-year-old Fred once again found himself traveling away from Baltimore and closer to his fears. He was going back to plantation life and its brutalities! What he had dreaded most had happened!

Thomas Auld had sent Henny, a slave girl with a disability, to his Baltimore relatives, since he had no use for her on the plantation. Hugh and Sophia Auld had kept her for a while, trying to fit her into their household. But they found that she could not function as a servant. They explained to Thomas that they would have to send her back to the plantation.

Angered, Thomas retorted that since they would not keep her, they would not be allowed to keep Fred. He demanded that they send the youth back to him.

Fred boarded the ship, tears misting and then filling his eyes and splashing down his cheeks. Now and then a muffled sob escaped him, despite his resolution not to cry. He just could not help himself. As he looked into the Chesapeake Bay’s depth, he felt slavery’s noose tightening around his neck once again.

Chapter 14

Once back on the dreaded plantation, Fred found it difficult to fit in. Most of the slaves welcomed him, but a few resented him because he’d lived in Baltimore and could read, despite the efforts that had been made to stop him. What really distressed him, though, was St. Michaels’ restrictiveness. In Baltimore he had grown accustomed to functioning

almost as a free person.

Now instead of working as a house slave, Fred toiled in the fields from sunup until sunset. Hunger, as well as cold and cruelty, haunted him, but there was no Miss Lucretia to soften slavery’s horror for him. She had been dead for several years. Worst of all, he had little access to books. Slavery, he feared, was consuming his mind and ambition, reducing him to a machine.

How can I be free? he brooded. How can Mr. Lawson’s prediction about my becoming a great man ever come true?

One night while gazing up at the heavens and planning ways to achieve his freedom, Fred saw an unforgettable sight. The stars, which a moment before had been stationary, darted with amazing swiftness and brightness toward earth. It seemed that the entire heavens would be emptied of them! From all over the plantation, slaveowners and slaves scrambled out to see the gigantic display.

“It’s judgment day!” some screamed.

Weeping and pleas for mercy sounded forth from the great house and slave quarters alike. But Fred, along with several slaves and a few children from the master’s quarters, could not contain their joy. They all joined together, holding hands and singing. Tears of joy trickled down their faces.

Yes, thought Fred, the Lord is returning! He remembered Jesus had said that the stars would fall just before His second coming. Any moment now He would take Fred and the others away from sin and slavery! Thank God, he would be free at last!

Hardly breathing, the group waited and waited and waited—but nothing happened. Smiles gradually gave way to perplexed looks, and laughter was replaced with a silence as quiet as the grave. Long after the last star had fallen, leaving darkness to enshroud the earth, they stood gazing into the heavens, still waiting. Jesus had not come back.

Overcome with grief, the group felt lost and unbearably alone. Unashamed weeping spread throughout their ranks, many of them wishing for instant death. Finally a slave crippled with age and supported by a homemade crutch cleared his throat.

“Jesus has been so good to us,” he began, tapping his hickory crutch with a gnarled forefinger. “He’ll never forsake us.”

Pausing to let his words sink in, he viewed the crowd earnestly. He seemed to forget his own disappointment in his attempt to comfort his hearers. “He didn’t go through all that suffering on Calvary just to have us stay in this prison down here!”

At this the crowd’s mood brightened, and a few hearty amens sounded. Like water rippling after a stone enters it, a wave of responses followed his words.

“Yes, God’s Word will never fail.”

“He delivered the Hebrew boys from the fiery furnace.”

“He that shall come will come and not tarry!”

“By and by, we’ll know why He didn’t come back.”

“Stay strong in Jesus.”

With hugs and handshakes all around, followed by one last, longing look upward, they disbanded, each person absorbed in his or her own thoughts. Fred stumbled into his cabin. It seemed that whenever he raised his hopes to escape slavery, something was sure to dash them.

For a few minutes he tossed on the bundle of rags forming his bed. Finally he turned on his back to look up at the thatched ceiling. Should he give up his plans for freedom? What about God? Of what use was He? Should he forget about Him, too?

A picture of Mr. Lawson

flashed through his mind, and Fred’s despair vanished. He

would never give up his fight for freedom! And he would never stop asking God to help him achieve it.

Chapter 15

Thomas Auld sat eating his breakfast fretfully. A young house slave stood beside him, a large fan in his hands. Pursing his lips to present a picture of attentiveness, the boy’s brown eyes moved in a continual cycle from Auld’s face to the food. Whenever he spotted the slightest hint of perspiration on his master’s brow, he vigorously waved it away. Otherwise, he fluttered at a stray fly or two threatening to light on the food.

Auld, however, seemed unaware of his presence. He rapped his fork on the table, muttering, “What can I do?”

It was young Fred that was the cause of Auld’s worry. Ever since Fred had arrived from Baltimore, Auld had been driven almost to despair by the young slave’s rebelliousness.

Arising from his unfinished breakfast, Auld wandered outside, wondering how to transform Fred into an obedient, hardworking slave. Eventually, Auld snapped his fingers and smiled. That’s the answer! he thought with relief.

Auld recalled that Mr. Edward Covey was an effective “slave-breaker.” Just as a skilled horse-breaker tames a high-spirited horse, Covey used an unrelenting series of brutal and nerve-racking strategies to make rebellious slaves submissive. He was so successful at his job that he was never short of such slaves on his farm. He kept them for one-year intervals, earning his wage for “breaking” them by their work on his farm.

It would be just the place for Fred, thought Auld. With a smile he turned and walked back inside, his appetite reawakened.

On January 1, 1834, Auld sent Fred to Covey’s farm. The first six months were the realization of the youth’s worst nightmare.

Three days after his arrival, Fred was given a team of unbroken oxen and sent into the nearby forest to fetch wood. The oxen became agitated, running at full speed against trees, damaging the cart, and almost injuring Fred.

Finally quieting them, Fred loaded the cart with wood he had chopped the day before, but the oxen spooked again. At the gateway near the farm the team ran as though their burden were straw. One of the wheels caught the heavy wooden gate and demolished it, and Fred was almost crushed in the fray. Frightened, he inspected the damage but felt that he could explain it to Covey.

“Get back to the woods!” Covey shouted, angrily brushing away Fred’s attempted explanation. “I’ll teach you not to waste time and destroy valuable property!” He drew himself up to his full five feet ten inches to emphasize his intention.

The same oxen took Fred into the woods. Mr. Covey followed close behind. Now, however, the oxen were models of obedience, having gotten the mischief out of their system. Fred realized that earlier he should have driven them around the open field before venturing into the woods. In that way they would have gotten used to him and prepared for their task.

Covey jumped off his horse once they reached the woods. Stopping near a large black-gum tree, he cut off three young branches with his jackknife, then rapidly trimmed them. “Take off your shirt!” he commanded, his eyes flashing angrily.

But I’ve done nothing wrong! the teenager thought, standing still.

Covey lunged at him, tearing Fred’s shirt off, and whipped him unmercifully. This was the first of many times he would flog Fred.

Not satisfied with beatings, however, the slave-breaker devised mental strategies calculated to strike fear and obedience in the teenager. He tried to make him feel as though he were always being watched.

Eventually, Fred’s every waking moment overflowed with dread of Covey. The slave-breaker always seemed to loom nearby with a new type of punishment. Hanging over all this was the reality of work, work, and more work that filled Fred’s days.

It was only on Sundays when Covey went to church that Fred got a break from his toil. On those days all he could think of was rest and sleep. The once-consuming desire to be free vanished. Reading and thinking no longer seemed important. He was broken at last.

Chapter 16

Six months after his arrival, Fred’s desire for freedom was suddenly reawakened. It happened when, overcome by nonstop work in the hot August sun, he fainted. Mr. Covey immediately appeared when he heard the machine used for the harvesting job stop.

After finding out that Fred was the reason the work had halted, he kicked the fallen youth twice in the side. “I’ve got something to cure your headache!” he declared. Then he struck him in the head with a hickory slab, opening a large wound. He left Fred bleeding and went to see how the work could continue. In Covey’s absence, Fred recovered sufficiently to run away to his master, Thomas Auld.

At Auld’s house, Fred hoped his bleeding condition would speak on his behalf against Covey’s inhumane treatment. At first Auld seemed moved at the sight of his injured young slave. Bit by bit, however, he hardened himself against Fred to the point that he declared that he had deserved the treatment.

“I don’t believe you were sick,” he accused. “No doubt you tried to escape work! As for what you call dizziness, it was caused by laziness and not by Mr. Covey’s disciplining you.”

Then he looked Fred in the eye. “Mr. Covey is a good Christian fellow. You’re in no danger at his farm. You must get back there! If you don’t, I’ll get hold of you myself!”

After a night’s sleep at Auld’s plantation, Fred returned to the slave-breaker, Mr. Covey. The teenager dreaded what would happen. He found the slave-breaker riding to church with his wife.

“Good morning, Fred,” Mr. Covey greeted him. “How are you doing?”

Fred was stunned. He waited, expecting any moment to hear the slave-breaker begin a tirade about his running away. Instead, Covey acted as if Fred had been there all weekend. The boy blinked. Never before had he seen such a Christian manner in Covey.

“The pigs have gotten into the lot,” the man continued. “See about driving the rascals out, would you?” With a wave toward the slave, he tapped his horses and rode off toward the church.

Fred stood still, trying to understand the change in the slave-breaker. Then everything suddenly became clear: just as Covey was on his way to church in his best clothes, he was only “wearing” his Sunday behavior!

On Monday the man’s true self indeed emerged, and with a vengeance. He sent Fred to the stable, telling him to get the horses ready for work. While Fred was about his task, Covey crept up behind him and attempted to tie his legs so that he could whip him. Immediately realizing what Covey was up to, Fred disentangled himself.

As the slave-breaker wrestled to regain advantage, something snapped within Fred. He was tired of being beaten! Tired of being treated worse than an animal! Tired of fearfully looking over his shoulders for an ever-watchful slave-breaker! He resisted the man with all his might. While the slave-breaker punched, kicked, and threatened, Fred stayed mainly on the defensive, blocking his attacks.

This went on for almost two hours, without Mr. Covey succeeding in whipping the youth, but suffering several bruises and cuts himself. Finally in humiliation the man gave up, huffing and puffing, “I wouldn’t have beaten you half so much if you hadn’t resisted me!”

Fred stared coolly at him, thinking, You haven’t beaten me at all, and I’ll never allow you or any other slaveholder to beat me again!

It was indeed the last time Covey attempted to whip the lad. For the remaining six months of his contract, he

kept Fred at arm’s length.

Ashamed that he had been successfully withstood by a 16-year-old slave, Mr. Covey did not breathe a word about it to anyone. He could not risk ruining his reputation. Slaveowners would stop bringing their slaves to him if they knew that he could not control a mere teen.

For Fred’s part, the battle renewed his self-respect, ambition, and determination to be free. He decided that he would not spend another day as a slave if he could help it. As soon as an opportunity for freedom presented itself, he would take it. And if it did not present itself, he determined that he would make one himself.

Chapter 17

It’s got to be different this time! the sailor thought, carefully eyeing the growing crowd at the Baltimore train station. None of them looked toward the dray* on which the sailor sat. Their entire focus was on reaching the ticket counter and boarding the awaiting train.

The sailor was a heavyset, muscular man more than six feet tall. He appeared to be in his early 20s, while the dray’s driver, a smaller, dark-skinned man, was in his mid-40s. Behind them was a battered seaman’s bag.

A few minutes passed, and then there was a sudden surge of activity. The crowd, a vast tangle of hurrying feet and package-laden arms, clamored to board the train. The train started, clanging and wheezing clouds of smoke into the morning air, ready to begin its journey northward.

In this flurry of activity the two men hurried forward almost imperceptibly. As the train started moving, the young man jumped agilely past the still-open door. At almost the same time the smaller man hoisted the bag aboard and then drove away without a backward glance.

Good, Fred thought, I’m safely aboard! If I had joined the crowd at the ticket depot, the conductor would have examined my borrowed seaman’s pass and discovered that I’m a runaway slave! May You bless Isaac Rolls for using his dray to help me get aboard.

He sank into a seat in the designated section for Black people and considered the events leading to his train trip. When Fred had finished his year with Mr. Covey, Thomas Auld had rented him out to another temporary master, Mr. Freeland. There, 17-year-old Fred had plotted with several other slaves to flee to the North via the Chesapeake Bay.

Just before the getaway, however, one of the conspirators informed Freeland of the plot. The plotting slaves were all thrown in jail. Eventually Thomas Auld secured Fred’s release. But because of the community’s hostility toward the slave, he again sent Fred to his brother Hugh in Baltimore.

During the next four years in Baltimore, Fred experienced less brutality. But, he thought bitterly, slavery is slavery—whatever its form! He therefore hatched another plan to escape, this time involving as few persons as possible.

Hugh Auld allowed Fred to find a job as a ship’s caulker as long as the slave bought his own clothes and food. He also demanded the rest of Fred’s wages each Saturday. Despite the hard bargain Fred still managed to save for his escape.

More than money was needed for his escape, however. He needed freedom papers. Several free Black friends were willing to lend him theirs so that he could pretend to be the person pictured on the document. After he was safe in the North, he could mail it back to the owner. Unfortunately Fred did not resemble any of his free friends enough.

Then he remembered another free Black friend, a sailor whom he had gotten to know in his job as a ship’s caulker. He had something Fred could use in his escape plan.

“I’m going to run away,” Fred began directly when he found the perfect place and time to reveal his plan to the sailor.

“When?” was all the man responded.

“This coming Monday, September third.”

“Doesn’t leave you a lot of time.” He frowned for a moment. “But how are you going to do it? Borrow someone’s pass?”

“Can’t. I don’t look like anyone who has one.”

“So are you going to lie low and travel by night, using the woods?”

“No, I’m going to travel by daylight without a pass.”

The friend looked at Fred as though the slave had gone crazy.

“Here’s my plan,” Fred explained. “I’ll pass myself off as a sailor. I already have a sailor’s outfit. All I need are your sailor’s protection papers. With them and my ability to talk like a seaman, I’ll board a train for Pennsylvania and freedom.”

The man looked at Fred, a smile slowly spreading across his face. The caulker was not crazy after all. Brave as a lion. Sly as a fox. But definitely not crazy.

He supported Fred’s strategy, especially since his own parents had been runaway slaves. He asked only that Fred send his papers back as soon as he had settled in the North.

Now on board the train, Fred mentally checked off the fact that he had finished phase one of his escape. But he could not take anything for granted. He had to be on the lookout for anything that could spoil his plans.

A loud, grating voice interrupted his thoughts. “Get your tickets out on the double!” the conductor commanded as he entered the car. He walked authoritatively among the passengers, taking their tickets and comparing the pictures on their passes to them.

Fred appeared calm, but inwardly he shook with fear.

The conductor now loomed before him. But as he looked at Fred’s red shirt, sailor hat, and necktie tied sailor-fashion, a smile replaced his gruff, commanding manner.

“How are you, sailor?”

“Fine, captain!”

When Fred didn’t reach for his free papers, the conductor said kindly, “Just let me see your free papers.”

“I don’t have them with me. I never carry them to sea.”

“But, of course, you have something to prove you’re a free man?”

“Yes, captain. I have a paper with the American eagle on it. That ought to carry me all over the world, don’t you think?”

The conductor smiled again. He glanced at the document and then passed it back to Fred. “Yes, it will, sailor. It surely will!” With that, he adopted his former manner and marched to the next passenger.

Last Chapter

Shortly after his arrival in New York in 1838, Frederick married his girlfriend, Anna Murray, a free Black woman from Baltimore. He changed his last name to Douglass (it was originally Bailey) to avoid capture, and he became a famous antislavery speaker, moving audiences to action through his firsthand accounts of enslavement. Throughout his long life, he fought against every form of oppression and segregation.

Frederick Douglass firmly believed that God guided his activities. He once declared that his childhood move from the plantation to Baltimore was more than luck or chance. Many other boys could have been chosen as caretaker to Tommy, he explained, but he “ever regarded it as the first plain manifestation of that ‘Divinity that shapes our ends, rough hew them as we will.’”

Among Douglass’ accomplishments are the following:

• In 1847 he started his own newspaper, The North Star, to give an African view of slavery and discrimination.

• He wrote three autobiographies: Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (1845); My Bondage and My Freedom (1855); and Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1881).

• His broad-mindedness led him to fight for women’s rights, as well as those of African Americans. In fact, the Equal Rights Party nominated him for vice president of the United States in 1872.

• His abilities led to government appointments as United States marshal for the District of Columbia (1877) and later as U.S. consul general to Haiti and charge d’affaires for Santo Domingo (1889).

• Following his death from a heart attack in 1895, many people, including government dignitaries, attended his funeral.

• He is buried next to his wife Anna in Mount Hope Cemetery in Rochester, New York.

Frederick Douglass’s life shows how God values and leads individuals. It also demonstrates what He can do through anybody dedicated to Him and all people.

3 thoughts on “The Winding Trail to Freedom, Chapters 1-18”

Oh thank you! I was in primary when this came out and never got to read the whole thing. I’ve read a couple guides with a chapter in them but never had all of them and I really wanted to read it. This means so much.😊

Oh my goodness! This story is soooo good! You are so talented! God bless your work! ❤️❤️❤️

Just so you know this is a true story.