In 1908 Charles Dawson, a country lawyer and amateur fossil hunter, was walking along a country lane in Piltdown Commons, Sussex, England. He stopped to watch a road crew working in a gravel pit. A workman threw out a reddish object, and Dawson picked it up.

“What’s this?” he asked a workman.

“A coconut, sir,” the workman said.

Dawson disagreed. “Stop! It’s part of a skull.” He examined the gravel pit and indeed found bone fragments from the top of a skull. The lawyer took the bones home to examine them more closely. Iron oxide in the soil had stained them dark red.

Dawson took the pieces of the skull to Arthur Smith Woodward, head of the Department of Geology at the British Museum. The skull immediately interested Woodward. It appeared very old.

Woodward and Dawson returned to the gravel pit and searched for other parts of the skeleton. They came across a peculiar-looking jawbone. It had teeth that appeared to be human, but the jawbone was shaped like an ape’s jaw. The strange shape of the jaw convinced Woodward that the skeleton was half man and half ape.

Woodward became excited about the discovery. He failed to notice that the jawbone had been stained by potassium dichromate, a chemical not normally found in the soil in that part of England. It seems odd today, but no scientist questioned how the bones had been stained with the chemical.

Fifty years earlier, Charles Darwin had proposed his theory of evolution. Since then, scientists had been looking for a direct link between human beings and subhuman forms.

None had been found. Up until that time, all ancient bones had definitely belonged to either an ape or a man. The Dawson bones was the only skeleton that appeared to be a mixture of both.

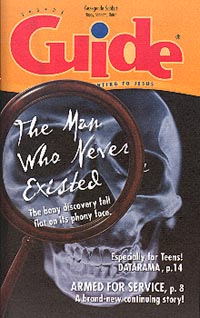

Dawson’s discovery burst upon the scientific world. The skeleton soon became known as Piltdown man, after the area where it was found. Woodward gave Piltdown man the scientific name Eoanthropus dawsoni, which means Dawson’s Dawn man.

One English scientist, Sir Arthur Keith, an expert on the brain, said, “The skull represents an extremely ancient form of man. It is the most primitive human brain so far uncovered.”

Scientific journals and textbooks published models of Piltdown man. The 1926 edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica carried an entire article about the skull. The British Museum proudly displayed the actual Piltdown skull, while museums throughout the world put plaster casts of it on display.

Yet the whole thing was a hoax. Piltdown man never existed.

In 1953 Kenneth P. Oakley and a team of researchers at the British Museum discovered the truth.

Oakley tested the bones with fluorine to determine their age. The top part of the skull, he found, came from the skeleton of a person who had probably died during the Middle Ages. The jaw came from an orangutan and was only a few years old.

The bones were reddish-brown as a result of the action of iron oxide in the soil. But the color was only surface-deep. A truly old bone would have been stained through and through.

The teeth of Piltdown man were black, but the black substance was only paint. Under-

neath the teeth still gleamed white.

The teeth showed heavy signs of wear–like human teeth. Monkeys, apes, and orangutans eat tender shoots of grass and fruit that do not wear down their teeth. Humans eat a variety of food, so their teeth wear down. Someone had filed the teeth to make them look human.

“The archaeologists who took part in the excavations at Piltdown were the victims of a most elaborate and carefully prepared hoax,” Oakley said.

Yet the fraud was not all that difficult to detect. The greatest scientists in England had examined the skull and other bones. They should have seen the deception.

Oakley’s revelation touched off a wild uproar. The British Parliament demanded an investigation. Scientists who had defended Piltdown man tried to hide their embarrassment, refusing to speak to reporters.

Scientists questioned who had produced the hoax and why. For years the lead suspect was Charles Dawson. However, those who knew him said he was an honest man. He could not be questioned because he had died in 1916, long before Oakley revealed the hoax.

In 1996 officials found a trunk stored at the British Museum that held a clue. Martin Hinton, a volunteer worker at the museum 84 years earlier, had owned the trunk. It contained bones like those found in the gravel pit.

An investigation revealed that Hinton had asked Woodward for a full-time job at the museum. Woodward had turned him down. Hinton may have been angry with Woodward and planted the bones at Piltdown, perhaps hoping to disgrace Woodward.

Regardless of the identity of the culprit, the scandal embarrassed not only Woodward but also the entire scientific community. They wouldn’t have been fooled if they had believed the Bible truth that God created humans in His image–not from the jaw of an orangutan.

Illustrated by Terrill Thomas